Oh, Death! Woah, Death! Won’t you spare me over ’til another year? -Dr. Ralph Stanley

Premonitions

It wasn’t like I didn’t know Dad was going to die. He even predicted it down to the day, at least for the first couple of times he passed.

It was a lovely autumn afternoon in September 2022 when I stopped by the Southwestern Virginia Mental Health Institute to attend a review with Dad and his care team. The precipitous decline in his physical health, which now bound him to a wheelchair and decimated his appetite, came on quickly since he returned to the hospital after a rough spring at his previous care center. He was now heavily medicated with Risperdal, an antipsychotic that seemed to be the only pharmaceutical left on the planet that could quell his remaining hallucinations and delusions. The meeting was productive, and we discussed discharge planning. Later, Dad patiently listened to me play the piano (which I do poorly on any day of the week), had lunch with my mother and me, and chatted about the family’s general goings-on.

I casually, if not with a little trepidation, reflected on his review meeting as I walked to my truck. He shared new stories about how his father beat him and his brothers when they were boys, and how it made him never want to spank his own children. He asked me to tell the care team it was true, which I did in a way as comically awkward as I could make it. After this, he had dropped the real mood killer, declaring that he wouldn’t live to the New Year. There was a certain degree of foreshadowing in how he said it, like he had the trip planned and was only waiting for his angelic Uber driver.

He moved out of the state hospital to a new care center with a dedicated dementia and memory care ward. It wasn’t perfect, but they could handle his unique behavioral health needs. The administration and nursing staff were amazing. The head doctor seemed less than ideal, though. We disagreed about who was in charge of making Dad’s medical decisions, even though he had a copy of the court order that clearly identified my brother and me as Dad’s guardians. This came to a head in December when the doctor decided, without our authorization, to drain a growth behind my Dad’s left ear. He insisted he could fix it, since, in his opinion, it was clearly recent. I had already told him twice that Dad had it for decades and that he wasn’t authorized to work on it, as it wasn’t the source of any of Dad’s health issues. He did it anyway, and the next day (the 20th), Dad lost consciousness for 24 hours.

Dad was awake and happy to see my youngest sister and me the following day (the 21st) when we stormed in demanding to know what happened. The cause of his unexpected collapse became all too clear when I saw the sutures behind his ear, and the bandages and bruises from his restraints. The charge nurse made no excuses for the doctor, who was allegedly gone fishing.

One week later, back in Knoxville, I jumped on my weekly video call with Dad and introduced him to my youngest daughter for the first time. He was having a little trouble figuring out who we were until the all-powerful magic of grandchildren seemed to revive him.

He was dead, to begin with…

My phone rang a few days later, on December 31st, and the nurse at the other end told me that Dad was on his way to the hospital. He had lost consciousness again, but this time, they didn’t do anything about it until the early evening when one of the nurses noticed his ragged breathing. His blood-oxygen level was dangerously low, and they put him on a respirator before eventually sending him to a hospital just east of Abingdon. The next few hours were a whirlwind, and someone from the hospital finally called me to let me know where he was and that he was mostly alive. His heart stopped once or twice, and they revived him before reaching out to us to ask what to do next.

Dad was true to his word and spent most of New Year’s Eve trying to die from an extremely bad case of double pneumonia and heart failure. The doctors revived him twice without asking for direction from the family, then called me demanding that I tell them to unplug his ventilator. I told them that if his heart went out again, they needed to let him go, but otherwise, since they brought him back and he was responding to treatment, no one was pulling the plug. As they explained the pressures and difficulties of running an emergency room, it became clear that they cared more about getting their bed back than the medical and moral dilemma they caused for us. So, the next morning, an entire contingent of Billingses camped out in his room and kept a near-constant watch on him for the next seventeen days while he recovered.

The first two doctors who saw Dad on New Year’s kept demanding that we take him off life support. The first stopped calling after I said no a few times, and the second vanished in a puff of smoke when I told him at Dad’s bedside that we “weren’t going to be killing anyone today.”

The next doctor who came by described himself as a “hospitalist.” He is possibly one of the most caring and thoughtful people I have ever met. Dad wasn’t a guy who needed to hurry up and die to this doctor. Instead, Dad was one of God’s children who needed his help to recover and, if it came to it, end life gracefully. This guy listened to our concerns, he hung out to see how Dad and everyone were doing, he called me after absolutely crazy long shifts – for both of us – to give me updates on recovery and talk about continuing treatment, and he started the long, hard discussion of what came next: hospice.

Dad pulled through, and on January 17th, 2023, he was discharged back to his care facility on hospice. He couldn’t eat anymore without assistance, and the hospital refused to give him an ostomy bag, which the doctor requested, because they were concerned that he would die during the operation. After learning more about hospice from the doctor and securing assurances from both the hospital staff and the staff at Dad’s care center that they would help feed him until he could no longer take nutrition, my siblings and I agreed to place him in the care of Blue Ridge Hospice. Making sure he had help eating from family, friends, and care staff seemed especially important to us since Dad was a man who spent his life feeding other people.

Blue Ridge Hospice was – is – amazing, and they understood all of our concerns. They took phenomenal care of Dad, supported the whole family, and relentlessly ensured he had everything he needed. This included working with the care center staff to schedule and administer end-of-life pain medication (morphine) and others to ease his passing.

I got a phone call from the hospitalist somewhere in the haze between when Dad was discharged, when I visited him at the care center, and when I made it back to my hotel room. The doctor reassured me that we had made the right decision, and he thanked me for partnering with him. He said that at every step of the way, I kept the hospital on its toes, both technically and morally. He told me that I “played it perfectly” and, despite the outcome (hospice…), I was a great champion for my Dad. He offered to be available to me if I had any questions, and I expressed our family’s extreme gratitude for the exceptional care and love he showed a man he didn’t know, as well as the warmth and kindness that he showed to us as he helped us out of the hospital.

Dad had a lot of energy after he was discharged. He even tried to stand and leave his room a few times. He watched TV, caused a little trouble, and flirted with nurses. Soon, though, the pneumonia came back. It was inevitable, I think, in the middle of cold and flu season during the COVID-19 pandemic.

My mother and I were standing outside the care center, taking a break and watching a light rain, when my sister called and asked us to come back inside because Dad was dying. She heard the death rattle in his breath. The three of us held him close, and he passed away in our arms. He was declared dead shortly after noon on January 29th, 2023.

Between Worlds

The movies always jump from recently dead to a graveside funeral with a bunch of posh, good-looking people in black suits standing around crying in the rain. Sometimes there’s a drunk leaning on a tree that saunters up to cause trouble in his cool sunglasses. There ain’t nothing in between in those movies; just dead, then the funeral.

In Dad’s case, the events following his death were, in a word, lit, and I will not recount them all here. I contacted the funeral home, which was expecting the call, and notified the rest of our family who couldn’t be there with us, triggering one of my siblings in a bad, bad way. The care center staff “kindly” reminded us every half hour that, since Dad was dead, they needed the room emptied by the end of the day. We stayed with the body until the funeral director and his man came to pick it up. They asked us to leave the room while they prepared Dad for transport. To be honest, that felt a little awkward to me, but I can understand it as a general best practice. I escorted them and Dad’s body to their vehicle, where I was surprised to see that they were in a late-model minivan instead of a hearse. I could imagine my Dad’s reaction since they had quite a distance to travel: “Bet that gets great gas mileage.”

Once the body was gone, I continued to make phone calls, we all packed my Dad’s things, and I assuaged the nervous care staff with sweet, sweet promises that we wouldn’t be there much longer. My mother and I were the last family to leave the center, about four hours and many such broken promises later.

I spent the next morning with the funeral director, a very lovely man who replaced one of my distant cousins in that role about a decade or two earlier. We considered his funeral home “our family funeral home” since so many of our loved ones passed through its doors. Almost nothing had changed since I was there for my grandmother’s funeral about twenty-five years earlier. Not even the table by the door with a little bowl of peppermints had been moved. It was still there, greeting visitors with a reminder that funeral goers need fresh breath, too.

The director and I worked through all the details in a few hours since my father’s instructions were simple enough: a cheap pine box, his white sport coat, money for the boatman, no ex-wives or girlfriends, no public, two songs, and a little lunch. Then we wrote Dad’s obituary. Dad got most of what he wanted, too, except the ex-wives part.

As soon as I finished at the funeral home, I checked in with my cousins to make sure we had everything we needed for the burial plot at the family cemetery. Then, I hit the road. I was desperate to get home to see my family and my doctor. I had developed a nasty infection on my hand that needed an antibiotic.

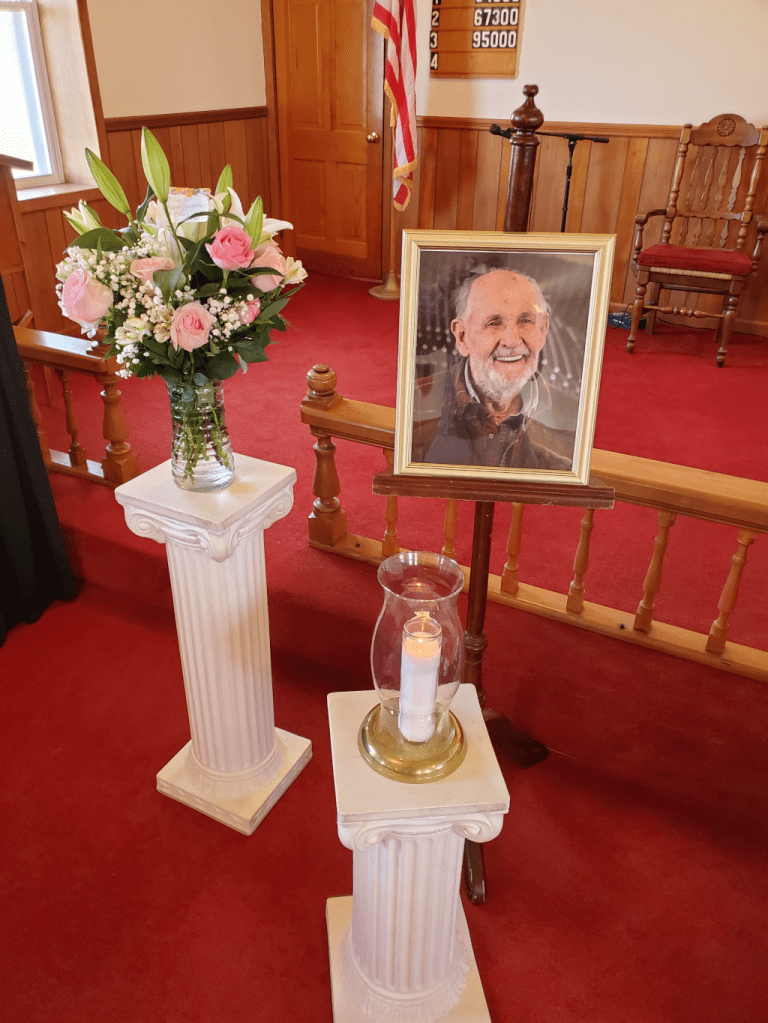

I was able to organize the rest of the funeral from home. It was a lovely, small get-together of family, some who knew Dad well and some who hardly knew him at all, but loved him all the same. There was a little bit of drama that required attention before and after the service. My poor mother was as tough as she could be until my Dad’s second song request started playing. She couldn’t hold back the flood any longer when she heard “He stopped loving her today” by George Jones come across the sound system.

Immediately after the funeral, and I do mean as soon as we started walking, my phone buzzed. It was my doctor: the infection on my hand was MRSA, and I’d need some stronger sauce to knock it out.

We carried Dad’s body to the back of the hearse, a beautiful late model Cadillac (which he also wanted), and walked through the cold winds of a western North Carolina winter to his grave a few hundred feet away. Graves are only dug to 58 inches, rather than 72 inches (6ft), for the safety of the grave diggers, and, finally, I understood why I always thought caskets seemed to sit too high when looking into a grave. After the graveside prayer, we took turns saying goodbye and casting shovels of dirt onto his casket. Few winds ever bit so coldly and yet so unnoticeably as the one that whipped my brothers and me as we returned to the church.

Dad wanted everyone to have lunch after his funeral, and my eldest sister organized the best funeral meal I’ve ever had. After lunch, I paid the funeral director $10000, then found some dessert and hung out with my cousins.

If you guessed that one of my Dad’s former paramours showed up unexpectedly and uninvited for lunch, you’re only half right. Two of them walked through the door mid-meal, together!

Buried in Paperwork and the Life Thereafter

I would be quite remiss in the telling if I let the story end there. First, there are many partings after the funeral of a family patriarch. Most are bittersweet because you just experienced great loss and sadness, but you’re happy to have spent it with those you love. Also, in my family, there’s usually “second lunch,” then a break, first and second dinners, and some sort of gaming until midnight. Some partings might be acrimonious, and a few are permanent.

You may recall the extensive list of legal and government services from my last post. They bring the excitement a few days later when you start contacting them all, they start contacting you, random people start sending you bills, you have to go to the courthouse, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

In our case, the greatest challenge was wrapping up Dad’s conservatorship. The guardianship closed very easily with a single report, but we spent the better part of two years closing out the conservatorship and setting up his estate with the last $650 he had.

What about those of us Dad left behind? How did we cope? You know, you get by. Lots of people told me different things that I really felt were bullshit. My doctor gave me the best perspective during my follow-up appointment for my infected hand. He didn’t say “You learn to live with it,” or ”Everyone handles it differently.” He told me that you take it day by day, some good and some bad, for the rest of your life.

And here I am, taking it day by day, and today marking the third year of Dad’s passing by finishing this series. I do things to remember him and pass on the lessons and wisdom he shared with me to my daughters or, honestly, anyone who will listen. He’s often in my dreams, and I fancy that sometimes, when I’m really about to mess something up, I can hear him saying in my ear, “Always wear your gloves, son.” I still cry sometimes, like now, when I think or write about it, or when I find something he gave me that I haven’t seen in a while. I laugh more, too, especially when my daughters do something that is so unmistakably “Papaw.” I cherish more moments of this short, lovely life, this blessing from God in all its wonder and beauty and majesty, when I see something and think “Dad would have loved that.”

That’s all, folks

Thanks for reading the final part of my series about my father’s struggles with cognitive decline and what we did to help him. I would especially like to thank my wonderful wife, Paige, for her support, Paige and my friend Brandon Nipper for reviewing drafts of my previous posts, and those who reached out after the earlier articles with kind words of encouragement and gratitude.

Those were the hardest days of my life, so far as I’ve lived them. I wrote this series to honor my father’s struggle and death, and as a means to process my own grief. I hoped, too, that by writing this, others might find something that helps them or eases their journey. And, maybe, in a way, this could be my attempt to copy the wisdom of the Bard in Sonnet 18: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, so long lives this, and this gives life” …to Dad.

You must be logged in to post a comment.